Think Tanks

Unravelling the definition of think tanks

An excellent place to start is by clarifying what a think tank is (although we avoid a rigid definition) and what it isn’t.

What’s in the name? +This section has been informed by the article Mendizabal, E. (2014a) What is a think tank? Defining the boundaries of the label. Learn more +This section is not intended as an in-depth review or critique of the term think tank. At the end of the guide you will find a list of further resources which we recommend to delve deeper in this debate.

Think tanks go by many names: think tank, research centre, public policy research institute, idea factory, investigation centre, laboratory of ideas, policy research institute, and more. In other languages, the list is even longer: centro de pensamiento, groupe de réflexion, Denkfabrik, serbatoi di pensiero to name but a few.

The concept of ‘think tank’ applies to different types of organisations with different characteristics depending on their origins and their particular development pathways. Think tanks set up in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century tend to be different from those set up in the latter part of the century. Their business models and organisational structures also differ greatly.

Organisations that call themselves think tanks include: for-profit consultancies, university-based research centres, international and national NGOs, United Nations bodies, public policy bodies, foundations, advocacy organisations, membership-based associations, grassroots organisations, one-off expert fora, and many others.

The definition changes with time and location and it usually incorporates aspects of the organisation’s context. Yet, all organisations labelled think tanks share the same objective of influencing policy and/or practice based on research.

Despite its plurality, it’s important to acknowledge that the term think tank was coined in the United States with an Anglo-American model in mind. And that model permeates and influences think tanks in different locations in various ways. Let’s start by reflecting on the mainstream definition of think tanks.

Defining think tanks +This section is not intended as an in-depth review or critique of the term think tank. For that we recommend the following resources: - Abelson, Donald E. (2009), Do think tanks matter? Assessing the impact of public policy institutes. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. - McGann, James and Johnson, Erik (2005), Comparative think tanks, politics and public policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. - Rich, Andrew (2004), Think tanks, public policies and politics of expertise. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. - Stone & Denham (2004), Think tank traditions: Policy analysis across nations. Manchester University Press. +This section has been informed by these articles: Mendizabal, E. (2010a), On the definition of think tanks: Towards a more useful discussion. Learn more +Mendizabal, E. (2010b), On the business model and how this affects what think tanks do. Learn more +Mendizabal, E. (2011a), Different ways to define and describe think tanks. Learn more

Think tanks are commonly defined as organisations that conduct research and seek to use it to influence policies (Hauck, 2017). Donald E. Abelson and Ever A. Lindquist (2000), focusing on North American think tanks, explain that ‘think tanks are nonprofit, nonpartisan organizations engaged in the study of public policy’ (p. 38). Stone (2001) defines them as ‘relatively autonomous organizations engaged in the research and analysis of contemporary issues independently of government, political parties, and pressure groups. This latter definition is widely used by think tank scholars and characterises think tanks as a clearly identified type of organisation, separate from universities, governments, or any other group. But the reality is fuzzier and think tanks that do actually fit the stereotype, such as the Brookings Institution and Chatham House, are less common.

Tom Medvetz, in the paper Think Tanks as an emergent field (2008), argues that Stone’s definition is limited because it +Click here for an interview with Medvetz. Learn more +Or read this article to explore this critique further Mendizabal, E. (2010a), On the definition of think tanks: Towards a more useful discussion. Learn more:

Privileges the US and UK traditions, where think tanks assert their independence more than in other regions.

Ignores that the first organisations to be recognised as think tanks, in the Anglo-American context, were not independent but the offspring of universities, political parties, interest groups, etc.

Excludes many organisations that function as think tanks.

Does not understand the importance of the concept and label in itself. Using the label (or not) is a political choice made by organisations embedded in a specific political context.

Think tank functions

Besides how they are defined, it is perhaps more useful to explore the roles and functions that think tanks tend to play. Think tanks have many roles and functions that vary based on the organisation’s context, mission and aims, organisational structures, business models, and even the resources they have access to. Their main functions include +These functions have been informed by papers from Belletini, 2007, Mendizabal & Sample, 2009, Gusternson, 2009, Tanner, 2002, Mendizabal (2010a, 2010b, 2011a) :

- Generating ideas.

- Providing legitimacy to policies, ideas and practices (whether it is ex-ante or ex-post).

- Creating, maintaining and opening up spaces for debate and deliberation – even as a sounding board for policymakers and opinion leaders. In some contexts, they provide a safe house for intellectuals and their ideas.

- Providing a financing channel for political parties and other policy interest groups.

- Attempting to influence the policy process.

- Providing cadres of experts and policymakers for political parties, governments, interest groups and leaders.

- Monitoring and auditing political actors, public policy or behaviour.

- Offering public and elite (including policymakers) education (something often forgotten by many think tanks due to the difficulty of assessing its impact).

- Employing boundary workers that can move in and out of different spaces (government, academia, advocacy etc.) and fostering exchange between sectors.

- Capacity building – designing courses open to interested audiences outside the think tank, creating fellowships and exchanging opportunities with both young and more experienced think-tankers.

- Participating in networks of organisations through which interaction is facilitated. For instance, the initiative Think20 Engagement Group brings together research institutes and think tanks from major countries to exchange ideas on pertinent topics.

Think tanks may choose to deliver one or more of these functions at different times in their existence. At times of political polarisation, it might make more sense to attempt to create new spaces for plural engagement. During political campaigns, think tanks can help develop ideas for political parties. During national or global crises, think tanks may be called upon to reflect on the causes of the problem to help focus future efforts.

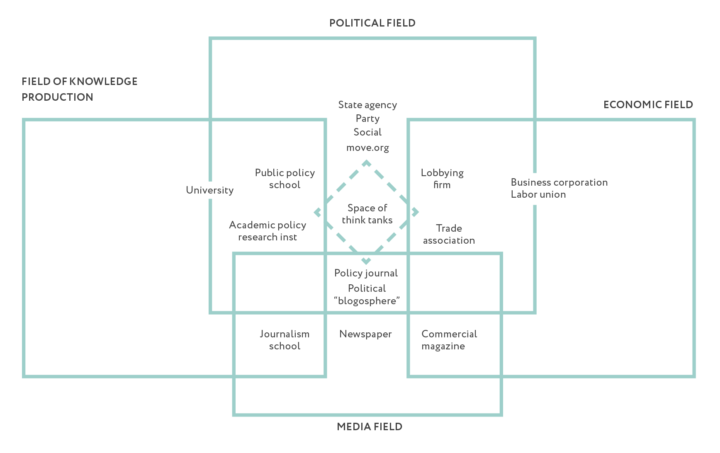

Medvetz (2008) hypothesised and sketched the positions of think tanks in the social space to assert that they are boundary organisations. They strive to assert their independence from other actors while also maintaining links with them. This representation reinforces the observation that think tanks’ functions are not static and are often exercised in relation to the functions adopted by others.

Figure: Think tanks in social space

Source: Medvetz (2008)

Source: Medvetz (2008)

Summing up

In summary, a strict and constraining definition of think tanks is of little help. Instead, think tanks are best characterised by a broad definition that emphasises the many forms, ties, ideologies, functions and roles that organisations can hold and play, and still be considered a think tank. They should also be understood based on the context in which they operate: a think tank in China need not be the same as a think tank in Bolivia (Mendizabal 2011b, 2013a) – and we should not expect them to.

Think tanks are a diverse group of organisations that have as their (main) objective to inform (directly or indirectly), political actors with the ultimate intention of bringing about policy change and achieving explicit policy outcomes. While think tanks inform their choice of objectives, strategies and arguments with research-based evidence, they are not independent from the influence of values. They may perform different functions: from aiming to set or shift the public agenda, and monitoring how specific policies are carried out, to building the capacity of other policy actors.

Types of think tanks +This section draws from: Mendizabal, E. (2013a), Think tanks in Latin America: What are they and what drives them? Learn more+Mendizabal, E. (2013c), For-profit think tanks and implications for funders. Learn more

The application of the different elements of a business model results in different types of think tanks. Stone’s (2005) classification, which relates to the think tank’s origin, is a good place to start. She identifies the following:

- Independent civil society think tanks established as non-profit organisations.

- Policy research institutes located in, or affiliated with, a university.

- Governmentally created or state-sponsored think tanks.

- Corporate-created or business-affiliated think tanks.

- Political party (or candidate) think tanks.

These are just some examples of types of think tanks, and many nuances exist within each category. For instance, within independent civil society organisations, some behave like research consultancies (undertaking research on demand and even bidding on calls for proposals).

This model tends to exist where international cooperation has played a significant role or where the main research funder is the state, via requests for expert advice or evaluations. These think tanks engage in service contracts to carry out long- and short-term research projects, and because of this, their space to follow their own agendas may be somewhat limited (Mendizabal, 2013a).

Some think tanks try to combine research consultancy with more independent type communication and outreach work. (Mendizabal, 2016)

Another example of organisations that fall somewhat outside Stone’s categorisation are the for-profit think tanks we have come across in Eastern Europe, Latin America and Africa. Their context has made this the most logical business model: high upfront costs for civil society organisations, regulations that limit their free functioning or access to data, complicated tax laws for the non-profit sector, and other factors, led them to opt for this model (Mendizabal, 2013c). Many figured that while governments may try to curtail civil society, they are unlikely to do the same with small and medium size businesses.

foraus is a Swiss think tank that was set up as a grassroot organisation and reflects its origins through its extensive network of volunteers who take on policy challenges and undertake research in a very collaborative way. They are supported by a small group of young think tankers who manage these processes and fulfil core functions.

These are just some of the options that exist. Your organisation could resemble any one of these or even be different. In any case, it is important to bear in mind that the business model should work for your organisational aims and the context in which you operate and that you expect to influence.

Box. Types of Think tank across the world

According to the 2019 Think Tank State of the Sector, which analyses think tanks around the world, the majority of think tanks for which there is data available are non-profit organisations (67%), followed by university institutes or centres (16%), government organisations (10%), for-profit organisations (5%) and a small group of other (2%). This also varies by region. For instance, in China the percentage of government think tanks is 74% while in the US and Canada 97% are non-profit. The legal registration of your organisation will need to adapt to the context in which it will operate (see What is the context? for more on this discussion)

Box. Think tank models in Zambia

As examples of the diverse types of think tanks that exist, we present a summary of different think tank models in Zambia (based on Mendizabal, 2013d and 2013e).

Academic think tank

These are the most traditional, and preferred by funders such as the African Capacity Building Foundation (ACBF). They follow an academic model and tend to be rather expensive (funding wise). ZIPAR (Zambia Institute for Policy Analysis and Research) is an example of this type. It had a slow and steady early start focussed on setting itself up: office, staff, systems, processes, partnerships, and so on, producing little or no outputs. This was made possible by core funding from ACBF. Up until 2013 it still had core funding from ACBF as well as from the government of Zambia, complemented by project funding from DFID and the Danish Embassy.

NGO think tank

An interesting example is the Centre for Trade Policy and Development (CTPD), which was born from the secretariat of a network of NGOs, working on issues related to trade and development. This secretariat started by doing mostly capacity building work, but it slowly shifted towards policy analysis and influence. The network members then became a board or assembly for CTPD. The organisation receives funding from international NGOs (some of it core funding).

Faith-based think tank

The Jesuit Centre for Theological Reflection (JCTR) has an interesting and uncommon think tank model: it is a faith-based organisation. It has the key advantages of having an established narrative and constituency. JCRT uses the Christian narrative, stories and metaphors, to communicate its evidence. This resonates strongly with many specialised and general audiences in the country. They have also developed a product: the basic needs basket. This is circulated and used in government, international actors, trade unions, media businesses, etc.

For more on religion and think tanks read these articles: Mendizabal (2012,) The church and think tanks and Mendizabal (2011), Is religion a ‘no no’ for think tanks?