How?

How will it carry out research?

Research is the cornerstone of a think tank. No matter the type of think tank, its aims, activities or business model, they all undertake some form of research. In this guide, we will not focus on research methods or type of research, but rather on how you can organise how it is carried out.

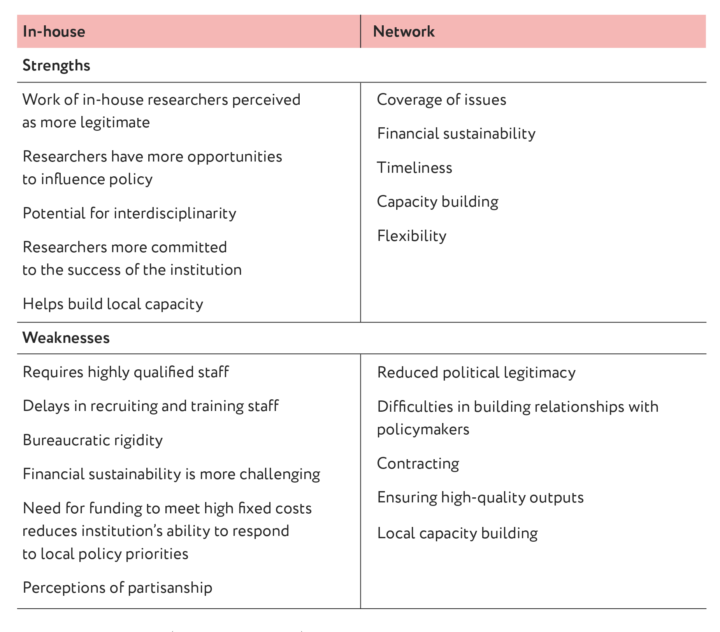

We have mentioned before that you can have researchers that are permanently employed by the organisation (in-house model) or work with external or associated researchers or consultants, national or international, hired to produce specific outputs (network model). Each has advantages and disadvantages (as seen in Table 1), and most think tanks rely not only on one or the other, but a mix of both (Yeo and Echt, 2018b).

Table: Strengths and weaknesses of the in-house and network models

Source: Extracted from Yeo and Echt, 2018b.

Source: Extracted from Yeo and Echt, 2018b.

Earlier, we mentioned the two different research models: the solo star model vs. the team model. In the solo star model, notable researchers work independently with the aid of research assistants. The personal agendas of researchers largely influence the organisation’s work, and given their prominence and respectability in the sector, management staff have less power to shift the agenda. In the team model, team members work in coordination with other centres or consultants (or among themselves) to produce their work. Think tanks with a team structure tend to lean towards conducting large-scale research projects, programme evaluations, and so on. In this type of organisation, the research agenda tends to be more centrally determined by the organisation.

Box.Balancing own research and consultancies

In this video Lykke Andersen, one of the founding members of INESAD (Bolivia) explains how to balance commissioned work and long-term research.

How will you ensure that your research is policy relevant?

To be relevant to policy and practice, research needs to be embedded in its context. It needs to respond to existing problems and be recognised by the stakeholders involved +It might be the case though that a problem is not recognised by the stakeholders involved but considered important by the think tank. In this case, if the issue is considered to be important by the think tank, then one of its first tasks will be to elevate it in the public agenda and to the eyes of the actors involved. . If a research piece is either too general or too specific it might not be useful or find a space in the debate. Applied research, which is the sort that a think tank does, aims to find solutions to a problem and therefore needs to be timely. If not, it might miss the opportunity to inform policy (Ordoñez and Echt, 2016b).

To be policy relevant, research should follow these principles (Ordoñez and Echt, 2016b):

- Be embedded in policy context.

- Be internally and externally validated.

- Be respond to policy questions and objectives.

- Be fit for purpose and timely.

- Be crafted with an analytical and policy perspective.

- Be open to change and innovation: as it interacts with policy spaces and policymakers.

- Be realistic about institutional capacity and funding opportunities.

Box. Toolkit for Political Economy Analysis

This toolkit is intended to help development projects achieve the best quality analysis and strong results: WaterAid (2015), Political Economy Analysis Toolkit.

Box. Policy questions are not the same as research questions

Based on Mendizabal, E. (2013f), Research questions are not the same as policy questions.

An important task for think tankers is working with policymakers to define what it is that they want to know and what information they need. If they focus only on what they say they want, a researcher misses out on uncovering what information is needed. A key skill for a think tanker is to unravel, with their stakeholders, what important questions need to be asked.

Policy questions are bigger in scope than research questions. To answer a policy question, many research questions need to be asked. For example:

Policymaker X might ask… But researchers might first have to answer …

- What skills needed to be developed to take advantage of the rise of new trading opportunities? Are we facing more competition from other neighbours than in the past?

- What specific sectors are under stress?

- Which sectors seemed to be emerging as future opportunities?

- What effects had domestic and international policy changes on these?

- Are our trade policy strategies and regulations ready to address future challenges and threats?

Think tanks’ comparative advantage lies, or should lie, in translating policy questions into research questions and research question answers into policy question answers. To do this they must behave as boundary workers: simultaneously working in the policy and academic communities (Mendizabal 2013f).

Positioning your think tank for policy influence +Based on TT Insight ‘Positioning think tanks for policy influence‘ Learn more

The Think Tank Initiative (TTI) supported policy research institutions across the developing world for 10 years. TTI learned that a think tank’s policy influence is shaped by many factors, but two of these are key:

- A reputation as an independent organisation that provides credible research: Independence rests on organisational strengths, such as having financial sustainability.

- The agility to navigate the local policy landscape and participate in policy debates: Engaging with policymakers early in the research cycle helps to ensure uptake, so the think tank has to be agile in responding to shifts in the environment and choosing the right points of entry. Think tanks can play a positive role engaging citizens, the media or advocates for marginalised groups directly in their research and in the policy process.

Therefore, achieving policy influence involves the entire organisation. The reputation for independence demands strengths across the think tank: effective leadership, financial sustainability, great researchers and administrators and the right skills in communications and networkers.

Research agendas +Based on Ordoñez, A. and Echt, L. (2016b), Module 1: Designing a policy relevant research agenda. From the online course: ‘Doing policy-relevant research’ and Weyrauch, V. (2015), Is your funding model a good friend to your research?

A research agenda is ‘a guideline or framework that guides the direction of the research efforts of an individual and/or organisation. It helps individuals and organisations communicate what they are focusing on and their area of expertise, and it also helps focus their research efforts and articulate different initiatives into common goals’ (Ordoñez and Echt, 2016b). It is not about producing a document and letting it sit. Research agendas are alive and active and they should guide the research that an organisation carries out. Agendas should be policy relevant, and for that they need to respond to the context.

When starting out you do not need to draft a lengthy document that outlines your research agenda (you can leave that for later) but it is a good idea to think about it, as it will give direction and purpose to your think tank. Your agenda should link to your aims and relate to your business model and funding strategies, as it will be affected by them. A think tank with core funding is freer to pursue their own interests, while contract or consulting think tanks tend to be more demand led.

When developing your research agenda, you should bear in mind the issues that interest you and the issues that are relevant in the context in which you wish to operate, but also the potential funding sources. The risk of building your research agenda in this autonomous way is that the topics and frameworks may not be completely linked to relevant stakeholders such as policymakers. On the other hand, funding based on grants or projects means you’ll have to be more flexible and open to addressing new topics or abandon others as you may have to adapt your agenda to donors’ priorities. Therefore, there is a trade-off between a more stable but less dynamic research agenda and a more flexible albeit less coherent research programme focused on projects.

Box. Components of a research agenda

There is no one specific way to draft a research agenda; depending on their characteristics and aims think tanks give prominence to different aspects. But in general, the following sections are recommended:

- Contextual justification

- Research priorities

- Conceptual or ideological approach (if it exists)

- Partnerships

- Funding sources

How will it ensure the quality of the research? +This section draws from: Baertl, A. (2018), De-constructing credibility: Factors that affect a think tank’s credibility. Working Paper 4. Learn more +Doing policy relevant research. Learn more +Think Tank Initiative in Enabling success.

Research quality, in the evidence-informed policy arena, is more than caring and ensuring that the methodology and process of a piece of research is sound, ethical, rigorous and unbiased. The literature on the subject identifies many aspects to research quality:

- Clear purpose and fitness for purpose. The questions that the research seeks to answer should have a clear purpose (of influence or action) and the research methods applied should respond to it.

- Relevance for stakeholders and policy/legitimacy. The research should address the needs of the stakeholders involved.

- Integrity and scientific merit. This entails the technical quality of the research: design rigour, conclusions following from analysis, transparency, and following ethical guidelines

- Quality assurance processes. The organisation must ensure that the research they produce fits all these quality criteria.

Box. The role of the research director

Diana Thoburn is the director of research at CAPRI, a public policy think tank in Jamaica. Read the full interview here.

My role as director of research is, broadly, to ensure that all the research we do and the reports we produce are done to the highest methodological and editorial standards. More specifically, I participate in determining our research agenda, conceptualising research projects, supervising researchers’ work from start to finish and editing the final report. I ensure that the organisation’s quality assurance protocol is adhered to and, as necessary, I engage in the research and writing myself. Finally, I represent the organisation in a variety of arenas, including presenting research results, whether on the media, to closed audiences, or at our public fora.

Options for ensuring research quality

Breaking down research quality into its component parts helps with planning for how to achieve it+We recommend exploring the Research Excellence Framework Learn more+and the RQ+ Learn more. For starters, working on developing a policy-relevant research agenda +For more on this you can inquire read the series Doing policy relevant research Learn more, as we discussed earlier, can help you identify gaps where research can be helpful. It can also help ensure that the research you will do is relevant to its stakeholders and to define the purpose of the research.

One thing you can do is work on developing a peer review process. This does not need to be applied to every piece of research that you do, but for important work you could have an internal peer review process in which researchers comment on each other’s work. Or you could have an external advisory group to advise on your research, not only after it is finished, but to ensure quality through the process +For more on peer review process read the series Peer reviews for think tanks Learn more.

You could also seek to collaborate with other research partners and academic institutions, especially on topics where you do not have internal capacity. This could help train your team and improve your organisational skills on specific subjects and research methods.

Finally, you should strive to develop a culture of evidence and quality data from the beginning. Discuss this with your team from the early stages and aim to grow and expand your quality control mechanisms as your organisation grows. Openly share your quality control mechanisms. This will be a signal to your partners and stakeholders that you produce quality research +Read the section on How will it ensure its credibility for more on this. .

Box. Do I need a peer review process?

The short answer is no, you do not need one. But it is a good idea to set one up for important work, and also to monitor the quality of your work and improve it. Setting a peer review process up also establishes an internal frame of mind that values and cares about research quality. It also signals credibility to your stakeholders (if you communicate it).

How will it be managed?

Without appropriate management, think tanks are unlikely to be able to deliver sustainable funding strategies, high quality research, and effective communications. Management involves various practical aspects of the organisation’s functioning: project management, budgeting, staffing, line management, and workspace, among others.

Budgeting +Read more about budgeting in Jones (2017), How to create a smart project budget for think tanks Learn more+and in Cardoso (2015), Managing budgets in a think tank. Learn more+You can also watch the webinar Smart project budgeting for think tanks. Learn more

Budgeting is more than an administrative task. Effective budgeting can make a huge difference to a think tank’s financial health, and sound financial management will allow the organisation to achieve its goals. Therefore, you need someone in your team with budgeting and financial skills. However, it is important that other members of the organisation who do not have training or experience in admin, can also understand or engage with it when needed.

A project’s life cycle could help to manage the project budget at department level in a think tank, following stages such as designing and submitting a research proposal, project initiation, project implementation, management and monitoring, and closure. Do not underestimate the importance of budgeting when preparing the following:

- Proposals for funders: it is important that the budget reflects the real costs of the project, including a share of the costs that are not directly attributable to specific research projects, such as staff costs, office rent, electricity, and others. You can add them as an overhead, under separate budget lines, or do both. You also need to separate out what is income and what are the expenses.

- Project budgets: transfer the proposal budget to a project budget template approved by the finance department. Keep the budget up to date and maintain an invoicing tracker.

- Budget monitoring: both the finance department and other project departments need to keep their own records of income and expenditure to provide an additional layer of quality control. Every financial movement should be recorded (plus supporting documentation). Also, a quarterly budget review process needs to be established to update all project finances.

- Project closure: projects that have finished in the current financial year need to be closed (balanced between incomes and expenditures, invoices sent to donors, expenditures completed, and fee information updated and finalised), but those that continue into the next financial year need to be reconciled (incomes, expenses and fee allocations updated). (Cardoso, 2015).

Financial management

Financial management entails strategic planning, organising, and managing the generation and use of funds in an organisations. And it is a key factor in ensuring the overall think tank sustainability. You should aim to find the right mix of actions and income sources for your organisation, bearing the following in mind ( Stojanovic, 2022):

- The activities fit your mission

- Ensure a combination of sources and types of funding (not putting all your eggs in one basket)

- The choices made allow the organisation to do its core work

Box. Reserves

‘A think tank’s reserves exist to cover expenditure in times of unforeseen crisis, either to deal with a shortfall in revenue, or to fund unexpected demands for additional work… they are crucial to both resilience and relevance. And, for this reason, the reserves policy is not an arcane topic to be left to the accountants on the finance committee, but rather a key management tool’, Maxwell (2021) Read more about reserves in this article.

Box. Guide for financial management

The following toolkits provide useful resources to strengthen your non-profit financial management:

Workspace

Although technically not a ‘how’ question, deciding on where to locate your operations is a management decision. If you have a comfortable budget, setting up an office will mostly entail choosing the best options that fit your budget. But as the COVID-19 pandemic showed, an organisation can very well function virtually. So if your funding and budget are small, investing in office space might not be worth it. There are many options available; you could seek to be hosted by an organisation that supports you and lets you work from their offices. Or you could work virtually and meet in rented spaces or even cafes. A virtual set-up works very well, especially if you opt for working with a network of researchers or in partnerships.

Going digital to save office costs, either until you have more funds or as a chosen strategy, is a great choice. Investing in a small office could equal the cost of a research assistant in many cities. And a research assistant is more important than an office. Also, it is possible to run an organisation remotely. There are several project management tools available. Dropbox or Google Drive can be your intranet; Slack is a great a team communications tool; Google suite solves your email needs +These are just a couple of suggestions based on our experience with these platforms. ; and teams can meet in coffee places and rent space for bigger meetings or events. Once you have secured more funding you can start looking for office space, but in the meantime going digital is a great option.

Line management +For more on staff see Who will work for it? (redirecciona a esta sección del guide)

Line management arrangements and processes are crucial to guarantee the effective functioning of teams and think tanks. They refer to the chain of command and relations of hierarchy within a think tank and a team. Even in circumstances in which researchers act rather independently from each other or from the organisation, or in horizontal business models, a minimum degree of leadership and line management are necessary.

Line management should focus on the most effective allocation of human resources to deliver the organisation’s mission, on supporting those resources, and on enhancing their capabilities. Good practice and literature on the subject suggest some of the following considerations in developing appropriate line management arrangements to lead and support teams and projects:

- No manager should line manage more than five people.

- Line management roles should be adequately resourced with enough time allocated to managers to work with and support their teams.

- Line management choices should not be driven by seniority imperatives but by the most effective use of talent to deliver project, programme and organisational objectives. Often senior and experienced researchers can play important roles as members of a team, and not necessarily as their leaders.

- Line management tools such as staff performance assessments should be used, primarily, to support staff development and overall team performance rather than for accountability purposes.

- Depending on the composition of teams, line management arrangements could include multiple management hierarchies. For example, a young researcher could be line managed by the leaders of more than one project (in a solo star model) and, similarly, a communications officer could be line managed by a research programme leader and the head of communications.

How will it communicate?

Starting out with your communications can seem daunting.+This section draws on Grant-Salmon (2014) Audience development: Can we have a meeting to discuss the dissemination of my research report? Learn more There is a lot of noise out there and making your research stand out among all this information can feel like an uphill battle. There is also the matter of figuring out where to start, who will be in charge, and what you will communicate. There are a lot of resources you can use to communicate your research, but before you spend a lot of money on a fancy website, set up social media accounts on various platforms, or plan a big launch event, take a step back and ask yourself one key question: Who has to engage with my work in order to get my desired impact? More often than not the answer to that question will take you directly to the correct communication tool or channel.

At the start of any project, think about what you are trying to achieve. What does success look like for your work? It is important to think about this at the start of a project. It will enable you and your team to choose the correct output to ensure maximum impact.

If you know your audience, you know how they consume information +If you do not know how your audience consumes information, do take some time in speaking with either your potential stakeholders or someone who knows the best way to communicate with them. . This will allow you to be innovative with your outputs and communication tools. It will also allow you to optimise your budget: it is better to have a small event (a breakfast meeting, for example) attended in full by key stakeholders, than a massive event where your stakeholders may stop by for a quick minute and leave without engaging. Your audience might consume information in the form of blogs, videos, briefings, virtual conferences, social media, press releases, backgrounders, infographics or one-to-one meetings – or a combination of several of these (Grant-Salmon, 2014).

After you answer this question, ask yourself: What is my budget for communications? It’s important to be realistic about what you can and cannot do. However, don’t make assumptions on costs. Don’t assume you cannot afford something just because it looks pricey or because bigger and/or older organisations can. Video is a perfect example of this: it is an excellent tool to communicate on urgent policy issues, yet organisations often think they are prohibitively expensive and shy away from producing them. Yes, they can be expensive, but you can also produce effective videos on a low budget. As with most things, it’s about doing the best you can with the resources you have available, and not aiming for a knock off. A video on a budget can look like a video on a budget and still be effective, engaging and impactful.

Box. Events

Producing events can be a cost effective way of producing new content. Here are a couple of ideas for doing so (Mendizabal, 2016):

- Search for free venues in your city. Universities sometimes lend empty rooms to their alumni, staff or students. Or you could co-organise with other think tanks – even coffee shops and restaurants lend themselves for events. Be creative and think outside the classic hotel venue and you will find many options.

- Events do not have to be elaborate; a simple room with chairs and space to present will do. And, if pressed for funds, limit the refreshments – people go for ideas, not for free breakfast (although in some contexts offering refreshments might be crucial so adapt this suggestions to your own environment).

- Keep events to the point, brief your speakers beforehand and allow plenty of time for the public to engage (and for networking!)

- Use the event as way of producing new content. You can record or web stream the event, live tweet it, upload or share presentations, write blogposts or reports on it, interview the panelists to create short videos, add attendees to your database, and so on.

An event is an incredible opportunity to do these and many other things; be prepared and think outside the box. Read more about events here: Mendizabal, E. (2015), How to produce a public event.

Deciding on tools and channels +Section draws from Mendizabal, E. (2012b), Communication options for think tanks: Channels and tools. Learn more +Weyrauch, V. (2014), Selecting different ways to reach audiences: A strategically ongoing effort. Learn more

There are a lot of tools and channels with which to communicate, but keep in mind that not all of them are appropriate for all projects (or all organisations). Each think tank has to choose the mix that works best for each project and for the organisation as a whole. There shouldn’t be a massive discrepancy between these two aspects. If your organisation is focused on specific themes and the work you produce is targeted at roughly similar audiences, there is likely to be a synergy between these two combinations. Larger organisations, however, are likely to have a wider scope on themes and research outputs and, consequently, their audiences, which means that the tools/channels combination will most likely be project-based (Mendizabal, 2012b).

The following questions can guide the process of choosing your tools and channels combination (based on Mendizabal, 2012b):

- Does the centre have the resources (funds and people) to effectively deploy all the chosen tools? For example: Does it have the media skills to deal with an important media strategy? How many events can it organise in a week? Does it have reliable access to the internet? Does it have resources for printing its publications?

- Are the tools sufficient to reach all of the organisation’s main audiences? Are any audiences not being reached through your choice of tools and channels?

- Do they offer the right balance between content and outreach? In other words, is it all repackaging or is there sufficient original material to carry the argument for a significant period of time?

- What will be the best way of keeping the organisation’s arguments and ideas on the public agenda for longer?

- Are the tools linked to and supporting each other or are they being deployed independently and in isolation?

Box. How to use your tools?

Based on Mendizabal. Communication as an orchestra.

The goal is to introduce your ideas to the public and keep them there for as long as possible, maximising your chances of being present whenever a window of opportunity opens. Think tanks need to keep their public engaged for prolonged periods of time. It is not good enough to get their attention once, at a press release or an event, never to engage with them again. They must keep journalists coming back for more, reporting on their ideas and recommendations; keep policymakers engaged in policy discussions over several policy cycles until the right policy window opens; keep other researchers involved in debates, and more. Their ideas have a greater chance of informing policy if they remain relevant and on the agenda for a long period of time.

This means that think tanks have to keep producing excellent communication outputs that they can combine to make ‘great music’ – music that is engaging, popular and interesting.

To help you with this, here is a chart showing the type of channels and tools available and how successful they can be at reaching specific stakeholders.

Table: Channels and stakeholders

Source: Weyrauch, 2014

The ‘classic’ model of disseminating information by think tanks (‘Expert or academic carries out research. Generates rigorous 40-page report. Comms officer is asked to promote said report. Launch event, press release, tweets. Maybe a video. Maybe an infographic’) is no longer sustainable. Tom Ascott +Ascott, T. (2019), New technology and ‘old’ think tanks. , digital communications officer at RUSI explains that this model is almost designed to be inaccessible to a larger and increasingly inquisitive public. Think tanks can’t rely on invite-only events or video uploads of those events. They have to compete with other online content creators and capitalise on modern digital media, turning research papers into multi-medium products.

Box. Tool: Communications health check

This tool is designed to help think tanks and research institutes to refine and improve their communications. It evaluates a number of key areas: audiences, channels, messaging, systems, strategy, capacity and monitoring.

By answering a number of simple questions, the health check will help pinpoint areas to consider prioritising to help you communicate your research and support your brand. The analysis recognises that communication is a complicated process involving strategy, tactics and resources: in other words, it is not all about output.

Size matters

When you are starting out, your communications department might look very lean. And by lean we mean a one-person show. What we do advise, and rather fervently we might add, is to do communications from the start. It might happen that you can only afford a communications manager or a communications consultant on a per-project basis. Whatever your reality is, don’t leave communications to the side. A 200+ page report doesn’t ‘speak on its own’. Neither does a 40-page document. Get your researchers on board. As Enrique Mendizabal argues in this video, ‘the thinktanker of the future is going to be a good researcher, communicator, manager and leader’.

Today’s researchers have to be prepared to wear different hats, but you cannot expect them to have the know-how already. This means you might have to invest in capacity-building opportunities to develop their skills. The bottom line is, big or small, when you are setting up a think tank you have to think about how your communications will play out: define who will be in charge and what resources she or he will have at hand.

Think tank branding

It is important for think tanks to work on their brand and ensure that they are more than a logo. Branding is key because your work as thinktankers needs to be communicated to wide audiences across different channels and it needs to carry your identity. In this article, John Schwartz explains that strong branding helps think tanks:

- ‘Become the organisations they aspire to be’: because the branding strategy extends the organisational strategy.

- ‘Own a piece of intellectual and cultural territory’: because it allows think tanks to know exactly who they are, what they are for and why what they do is important.

- ‘Produce the right kinds of communications for the right audiences’: because in order to build a brand, think tanks need to start with a good understanding of their audiences and how to communicate with them in an efficient and impactful way.

Box. Communicating research: Research isn’t linear, so why are reports?

Joe Miller makes the case for moving beyond PDFs when writing up research because they ‘box in our thinking’: they create linear narratives.

It is important to choose different tools for different communication strategies. In his article, he talks about a design based on the ‘choose-your-own-adventure’ approach: a website that allows readers to access the content from different entry points and to follow new links that might be lost in a linear PDF.

Think tanks should be creative and make use of engaging technologies, data visualisations and websites to communicate research findings.

How will it monitor its progress?

It is never too early to start thinking about monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL).+This section draws on: Lomofsky, D. (2016), Monitoring, evaluation and learning for think tanks Learn more +Lomofsky, D. (2018), Series on MEL for think tanks: Conclusion Learn more Measuring the impact and results of the work of a think tank is challenging, as these things are often intangible (e.g. building relationships with policymakers, playing a key role in debates or networks, etc). The ultimate goal is policy change, but this takes a long time and often cannot be attributed to a specific action, or organisation. Policy change is the result of many factors and actors (Lomofsky, 2016).

A good starting place is to define what success looks like. For this you must reflect on where you locate yourself in the policy process with any particular issue (Lomofsky, 2016). A think tank should not only focus on ‘driving direct policy change but also try to affect what happens before, throughout and after a new policy is designed. For example, to illuminate the way some policy problems are perceived’.

Aim for a balance between accountability requirements and honesty about achievements. This can be done by:

- Clarifying your policy influence objectives (they need to be realistic). These should be drawn from your mission, projects and the problems you are trying to address.

- Selecting your policy influence strategies and how can this be measured (e.g. advocacy, communications, capacity building, etc.)

- Ensuring you have the necessary resources to achieve results.

When think tanks devise good monitoring and evaluation plans, and when they carry out changes and improvements based on the lessons from the MEL exercise, they will be more effective in achieving their objectives (Lomofsky, 2018). A think tank can target this exercise for different areas of work: MEL of research quality, MEL of communications, MEL of governance and MEL of projects.

You need to reflect on what your organisation is already doing in terms of MEL and consider why you want to invest in monitoring your work + For more on monitoring and evaluation for think tanks read the series MEL for think tanks. Learn more. MEL for think tanks can have three focuses:

Policy influence (MEL-I): this will be discussed in the second session.

Communications (MEL-C): focussing on evaluating and learning from comms strategies.

Management and operations (MEL-M): this is about human resources, finance and internal operations.

Box. Toolkit: How can we monitor and evaluate policy influence?

CIPPEC has prepared a short toolkit that includes the various factors in the monitoring and evaluation of policy influence: organisational assessment, the basis of a MEL system, indicators, data collection methods and knowledge management, and more.

Based on previous work by Lindsay Rose Mayka (2008), the toolkit explains that there five reasons to conduct evaluations:

• Accountability: to provide donors and key decision-makers (e.g. board of directors and/or donors) with a measure of the progress made in comparison with the planned results and impact.

• Support for operational management: producing feedback that can be used to improve the implementation of an organisation’s strategic plan.

• Support for strategic management: providing information on potential future opportunities and on the strategies to be adjusted against new information.

• Knowledge creation: expanding an organisation’s knowledge on the strategies that usually function under different conditions, allowing it to develop more efficient strategies for the future.

• Empowerment: boosting the strategic planning skills of participants, including members of staff engaged in the programme or other interested parties (including beneficiaries).

Incorporating MEL into the daily life of any organisation is well worth it. A smart and proportionate use of MEL tools, and especially a well-thought-out MEL plan, can help think tanks to:

- Reflect on and enhance the influence of their research in public policy.

- Satisfy their (and their donors) interest in evidencing the uptake of research in policy.

- Build their reputation and visibility and attract more support for their work.

- Generate valuable knowledge for all members of the organisation.

- Re-organise existing processes for data collection so that they can be useful for real MEL purposes, and discard processes and data that are not useful.

MEL strategies can be carried out in a variety of ways, but it is important to understand the reasons for the MEL effort to best adapt the strategies and methodologies used to the type of knowledge to be acquired.

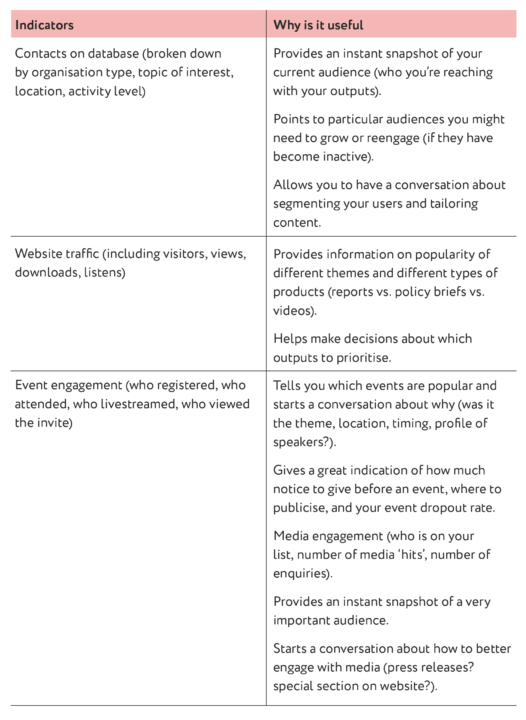

Monitoring your communications +Based on Monitoring your communications: Try this by Carolina Kern (2017). Learn more

Carolina Kern offers some recommendations for designing a MEL strategy for communications, especially for new and small think tanks:

- Be fully clear about what you’re going to measure and why. You can do this by revising your strategic aims or policy influence objectives.

- Don’t do anything too fancy to begin with. Pick a couple of indicators and use simple tools to track them. What you choose to monitor and which indicators you use will vary, but the most useful for those new to MEL for communications are shown here:

- Have a regular (e.g. once a quarter) meeting that focuses on learning and future strategy. You can present your data in a visually engaging way to show trends and use the meeting to brainstorm ideas for future communications and to fix any issues that may have come up.

Having a clear MEL strategy can be time consuming, but it is one of the best ways to help think tanks achieve the greatest impact in the most cost effective way as long as the data collected is analysed and the lessons learnt put to use.

This Communications monitoring, evaluating and learning toolkit based on internal guidance from ODI provides a framework to think about your strategy and offers questions, indicators and tools to help. It can help ensure that your communications are strategic and that you learn from what works and what doesn’t.

How will you ensure its credibility?

To inform policy and practice think tanks need to be perceived as credible sources of information and advice.+This section draws from Baertl, A. (2018b), De-constructing credibility: Factors that affect a think tank’s credibility. On Think Tanks Working Paper 4. Learn more Credibility qualifies think tanks to be consulted on and invited to participate in policy processes. It makes them attractive to funders. It promotes engagement with the media as experts in their field and facilitates access to reputable networks. Without credibility, none of this can occur, so it is a good idea to work on it from the moment your organisation is set up.

But how to do this? And more importantly, what is credibility?

‘Credibility is relational and it entails trust and believability. To be credible, an organisation or person needs someone to trust and believe in them … A credible person or organisation is trusted to have relevant expertise, and believed to be able and willing to provide information that is correct and true’ (Baertl, 2018a).

The paper De-constructing credibility (Baertl, 2018b) identifies 10 factors that individuals draw from and focus on (in various degrees) to assess the credibility of a think tank. These are:

- Networks. Connections, alliances, and affiliations that an organisation and its staff and board have.

- Impact. Any effect that a policy research centre has had on policy, practice, media, or academia.

- Intellectual independence. Independence in deciding their research agenda, methods, and the actions an organisation undertakes.

- Transparency. Publicly disclosing funding sources, agenda, affiliations, partnerships, and conflicts of interests.

- Credentials and expertise. Collected expertise and qualifications that a think tank and its staff have.

- Communications and visibility. How and how often the think tank communicates with its stakeholders.

- Research quality. Following research guidelines to produce policy-relevant research in which the quality is assured.

- Ideology and values. Ideology and values are the set of ideas that guide an individual or organisation.

- Current context. The current setting in which a think tank and its stakeholders are immersed.

To ensure and safeguard your credibility, the public needs to know that your organisation is transparent and intellectually independent. You could use your partnerships, affiliations, and board members to increase your credibility (drawing from the reputation of these organisations). You can also work on establishing and communicating your quality assurance processes. Don’t forget that the key asset in all of this is the people that belong to an organisation – they are the ones who impact whether credibility is maintained or not.

You can read more about think tank credibility in this annotated reading list that reviews academic and non-academic resources and offers an overview of the subject.

Box. Transparify integrity check

The Transparify integrity check is a (downloadable) tool that provides scenarios that will help thinktankers think through reputational risks and prevent reputational damage.

Box. CGD’s approach

Based on Mendizabal, E. (2014 d), A few initiatives, not many projects, may be the secret to success.

CGD has an interesting approach. Researchers do not have a list of topics but instead focus on one or two key initiatives over a relatively long period of time. These initiatives allow them to organise and allocate cross-organisation resources in ways that other think tanks can’t. They bring together people, research, communications, networking, management, and other ‘assets’ think tanks have to carry out their missions (Mendizabal, 2014d). They describe initiatives as:

… practical proposals to improve the policies and practices of rich countries, international bodies, and others of means and influence to reduce global poverty and inequality. Initiatives draw upon the Center’s rigorous research and utilize innovative communications and direct engagement with decision-makers to change the world. (CGD)

In the essay Building a think-and-do tank: A dozen lessons from the first dozen years of the Center for Global Development (MacDonald and Moss, 2014) (the updated version of 12 steps on policy change, Levine and MacDonald, 2014) the authors present lessons, based on their own experience, on how think tanks can organise themselves, how they can seek to bring about change, and how they measure success.

We present them here arranged into the three groups mentioned above (although there are clear overlaps):

On organisation:

- Start with flexible money, but not too much: use small amounts of flexible money as venture capital. This will depend on the type of organisation you are trying to create, but ideally aim for an ample and diversified portfolio of financial support. CGD found that a good mix for them was 3/4 programmatic funds for specific work and 1/4 unrestricted funding to be used for new programmes and ideas.

- Hire great people and give them plenty of freedom and responsibility: at all levels, senior and junior, full-time staff and associates. An interesting mission, worth fighting for, as well as a nice work environment will help to attract great people. This requires a good work environment.

- Share leadership: give staff, at all levels (don´t forget juniors as well), responsibility for running the think tank (or at least their bit of the think tank).

- Don’t plan, experiment: because this lesson seemingly goes against much of what you will read it is worth quoting the authors on this one: ‘Our strategy, so to speak, is to be ready to react to the sudden appearance of a policy window by having a good stock of well-researched ideas and providing our fellows with space to respond’.

- Partner with people, not organisations: it is easier to align interests between people than between organisations. Again, a quote on this lesson: ‘We’ve found that the best partnerships are those with very clear, narrowly defined objectives. We partner with a specific purpose in mind, not just to be part of a broad coalition’

- Resist the growth inertia: there may be lots of important issues and policy processes but they may not all be right for you. Identify the organisational size you are comfortable with. In CGD’s case maintaining a family-like culture was key.

- Make it fun: a good sense of humour should be a key ‘competence’ in any job description. And beyond fun, CGD strives to be a collegial place.

On bringing about change:

- Start fresh to stay fresh: be careful of becoming set in your ways. Encourage new ideas and ways to carry out your work and organise your think tank’s operations.

- Articulate an inspiring mission and aim for results: don’t just aim to know more – what will you do with this knowledge? Your mission should help guide your work, and keep you focused on a goal.

- Share ideas early and often: think out loud and benefit from feedback and growing support and expectation for your future results; don’t wait until you’ve crossed all the ‘t’s and dotted all the ‘i’s: it will be too late by then.

On assessing success:

- Celebrate and try to measure success: although measuring success in the evidence to policy environment is difficult, it is much easier when you have a clear sense of why you are doing what you do. What is that new world you want to see? CGD have also tried different (and tailor-made) trackers to understand and measure their impact.

- Keep asking tough questions: don’t be afraid to rock the boat, both your own metaphorical boat and other people’s. You don’t need to know the answers to all the questions, just keep on asking them.

IRADe’s case in India: What makes the think tank credible

Dr. Jyoti Parkih is a founding member and director of IRADe, a think tank in India. He was interviewed by Annapoorna Ravichander and shared what he believes makes IRADe credible and how they achieved this credibility. Read the full interview here.

According to Dr. Parkih the following reasons make IRADE credible:

- Strong focus on multidisciplinary research and analysis

- Evidence based scientific research and sound policy advice/measures

- Working simultaneously at local, national, regional and global levels and trying to converge in thinking and approach, thereby shaping policymaking at all levels

- Consensus building approach by involving all stakeholders and groups of interest

- Strong linkages with policymaking communities

- Extensive assignments with government, ministries and other governmental departments

- Cross-sectoral analysis and generating holistic insights/understanding

- Mix of research and action related work

Establishing credibility is a continuous process. IRAde build its credibility by:

- Being competent and becoming an expert in our field in the areas of modelling and driving regional energy co-operation, gender aspects, etc

- Having the ability to analyse an issue/situation and develop several potential solutions/options and tailor-made recommendations

- Doing rigorous work, and by publishing in journals and other publications

- Being people-centric and consistent in the approach.

- Continuing focus on multidisciplinary research and analysis

- Thinking globally and acting locally

How will it adapt to change?

As we discussed at the beginning of this manual, think tanks are a product of their context (see about the importance of understanding your context).+This section draws on: On Think Tanks Annual Review 2019–2020 on technology. Learn more +On Think Tanks Annual Review 2020–2021 on change. How do think tanks react to or foster change? Learn more Global changes are affecting the way think tanks operate, see themselves, and engage with their audiences. Here we present some of these changes through the eyes of think tank experts.

The future of think tank functions +Based on Mendizabal, E. (2021), The future of think tanks. Learn more

Mendizabal argues that the future looks bright for the functions that think tanks fulfil: developing solutions to social, economic and political problems; informing decision-makers and the public; promoting ideas; advocating for change; holding decision-makers accountable; training the next generations of decision-makers; creating spaces for informed debate on matters of public interest; and so on. But think tanks as we know them are changing:

- The skills of thinktankers are changing. While think tanks used to prioritise academic qualifications, it is now recognised that it is essential to combine a number of skills such as communications and networking. This means that there are also increasing efforts to participate in activities other than research, such as improving engagement with the public and shaping new narratives.

- The socio-economic make up of think tanks is changing in terms of a (too slow) incorporation of women and younger thinktankers into all levels and aspects of think tanks. And there seems to be a recognition that think tanks need to shed elitist credentials and work to include more culturally and ethnically diverse teams that are more representative of the public they intend to serve.

- Think tanks are facing competitions from individuals who use their analytical skills, use of databases and great command of new communication channels and tools to participate in public debates and who have displaced traditional scholars from spaces previously reserved for ‘experts’.

- Think tanks may, therefore, look very different in the future. Mendizabal argues that, first, there will be greater diversity in the types and structures of think tanks and, secondly, there will be more temporary think tanks that will run parallel projects or split and form new ones, experimenting with approaches and partnerships.

New ways of developing policy and programme options + Based on Struyk, R. (2021), An evolving wave in think tank policy development. Learn more

Over the last decade, policy development in think tanks has been changing. Traditionally, think tanks would identify the most desirable policy/programme through a process that broadly consists of:

- The problem being defined qualitatively and quantitatively.

- Options for addressing it defined after conducting the analyses.

- Criteria for assessing the efficacy of all options defined and applied.

- The most effective option identified.

- Senior level officials and concerned interest groups consulted and the final choice made.

This process includes little consultation with grassroots organisations working with the intended programme/policy beneficiaries.

Over recent years, a new approach has been adopted that varies from this model because

in-depth consultations are held with front-line administrators, eligible households or other beneficiaries. Additional data is collected through surveys of these stakeholders to assess inefficiencies. The implementation of pilot programmes is also common so that processes can be monitored and improved.

What this means is that a broader range of actors come together to co-create the intervention so that policy options are built from the ground up.

Most think tanks are not yet adopting this approach but two organisations that are doing so are the Results for Development Institute and New America.

From ‘think tank’ to ‘change hub’?

Anne-Marie Slaughter, CEO of New America argues that think tanks need to redefine themselves to adapt to this century. Watch her keynote speech for OTT’s Conference 2021 here.

Slaughter argues that we need to rename and redefine ourselves for this century because the concept of a think tank is a 20th century concept. She proposes the term ‘change hub’ as a shorthand for ‘public problem-solving organisations’. In her talk, she makes three points about why think tanks need to change and adapt to this century and how this is already being done.

- Defining her organisation, New America, as a ‘public problem-solving organisation’, contrasts with the way that American think tanks typically define themselves (often ‘policy research organisation’). This way of presenting the organisation shifts the focus away from policy because, she argues, if we focus on policy that means that we are aiming for change from the top down, as it is governments who enact and implement policies. It also means that we are typically located in capitals and that we are a very specialised group of people who focus on their particular areas. Being a public-policy problem-solving organisation means going beyond policy.

- How are public problem-solving organisations different from other organisations such as charities? Think tanks do focus on thinking, knowledge and ideas because ideas matter and drive action, but those working for public problem-solving organisations are thinkers who are more wedded to action than academics and whose solutions and recommendations are deeply rooted in thought.

- Think tanks are developing better ways of thinking by integrating thought and action in new ways. Many are now defining themselves as ‘think and do tanks’ or ‘think and action tanks’, and adopting a more bottom up strategy directly connected to people. This approach means moving away from traditional ways in which think tanks work, but although the process is different, the goal is the same: to support policy and practice with evidence.

Therefore, the label that we use matters. Something that may come to mind when you think about ‘think tanks’ is something closed or impermeable, like a fish tank or a military tank. And this is the way it seems to be in Washington D.C:, where the think tank system is mostly white, far more male than female, and does not resemble the plural country that the US is. So Slaughter offers a version of what think tanks could become – a different label that incorporates a different theory of action: using the label ‘change hub’ as shorthand for ‘public problem-solving organisations’ (just like think tank – is the shorthand for policy research institute). Why ‘change hub’?

- A hub is a place that connects many different people and networks.

- A hub is open – it invites many different kinds of actors, such as partners on the ground and many other intermediaries.

- A hub is a place where ideas and action come together in ways that create a fertile environment for change.

A change hub because as important as thought is, to adapt to our current context, thought must be connected to a direct theory of change. What we sell is ideas married to action for the purpose of change.

What is clear is that think tanks must evolve if they want to thrive. Mendizabal (2016) explains that, in the long run, the most successful think tanks are not necessarily the most popular, but ‘those that have designed effective and flexible governance structures. Those that have scoped and delivered the most relevant and robust research agendas. Those that have told a compelling story about why their evidence matters to the key people they want to reach.’

These think tanks are the ones who are most innovative in trying out new methods, communications channel and tools, and technologies. They are the most proactive in trying to find new sources of income or funders and exploring new business models as environments change.

How will it engage with evolving technology?

Technological advances are causing think tanks to rethink what they do, their business models, their research agendas, how they communicate and with whom, and what skills they need in their teams.+Based on:Tanner, J. (2020), Think tanks versus robots: How technology is likely to disrupt think tanks and Mendizabal, E. (2020), Editorial, in OTT’s Annual Review 2019–2020: Technology. Although we do not yet know the many ways in which these innovations will disrupt our lives, we are witnessing that technology is rapidly changing the way many think tanks operate.

Tanner (2020) suggests that think tanks in the 2020s will thrive if they can grasp how new technologies will change the way they work and adapt accordingly. Here are some of the ways in which think tanks work may be disrupted by technology in the coming years:

There is a great opportunity to produce research about the implications and applications of technology. Not only in how technology affects sectors like education or health, but also in the use of new technologies such as big data or machine learning.

New technologies will bring new ways of conducting research. The ability to understand algorithms will be key in understanding how the world around us is constructed.

New ways of communicating and of consuming information means that different skills and approaches are needed from communicators, who will need to carefully think about how to frame emerging issues in post-truth and mistrustful environments. Similarly, there is a decline in the centrality of text in favour of audio, and podcasts and live videos will be much more important in the coming decade.

It will be easier to create and operate think tanks with staff located all over the world using new software and more flexible administrative burdens.

Take some time to reflect on how you might incorporate these new technologies into your operations and whether this is an issue that you would be interested in researching. Also, consider including in your team staff with tech expertise and the skills to stay up to date on technological advances. Few think tanks have yet started working on identifying the many ways in which technological innovations might change our societies to provide guidance to policymakers and inform debates on the many dimensions that governments will have to grapple with.

Box. Data collection in the time of COVID-19

Paul Wang and Krishanu Chakraborty from IDinsight discussed about data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic. Listen the full interview here.

Krishany Chakraborty: I am based on New Delhi. The objective of the Data of Demanding is to make original primary data collection more debugged, faster, cheaper and also maintain a high-quality part from the data that is coming. This is very important even before COVID and still is very relevant because normally the data cycle for primary data has been really slow, it is very expensive and more less suffers from the same quality problems …. We are trying to solve this problem through a combination of technological and technical innovations that we have of real strong data system that we have and then rely primarily from the data collection …. We have primarily focus on helping development monitoring programs in about 27 of the poorest districts of India. We have been doing this for about two years, apart from other different projects across nutrition and health trying to provide data which is very fast, cheap and of high-quality.