Communications

Who will engage with it?

Think tanks need an audience to fulfil their missions. When exploring your context you should identify your main audience and who will be interested in what you have to say. Identifying who will listen to your think tank relates to the question of what it will aim to influence, the policy debates your aim to contribute to, and the policy level you wish to influence (national, local, etc.)+This section draws from: Mendizabal, E. (2013i), Think tanks and their key audiences: What do they have to say? Learn more+Grant-Salmon (2014), Audience development: Can we have a meeting to discuss the dissemination of my research report? Learn more.

Start by identifying who is interested in the issues your think tank is working on; who are you aiming to influence and who can support you in that process (e.g. media, funders, NGOs and opinion makers)? Remember that your audiences are not only policymakers, civil society and the media. Other thinktankers and donors (to name a few) also play a role. There are many tools available to help you in this process (see Box 27) – but don’t get overly focused on an exhaustive process at the beginning.

The question of who will listen to you is also relevant to your research uptake strategy. It is important to involve or consider your various audiences throughout the whole process to ensure that the research is relevant to their needs and interests +For more on research uptake read Mendizabal, E. (2013), Research uptake, what it is and can it be measured Learn more.

A good suggestion is to approach your audiences and ask them directly:

- How do you prefer to access new ideas and knowledge?

- How could think tanks communicate better with you?

- What examples can you share of good and bad experiences with think tanks?

Their answers will help plan your engagement with your audience. For example, a Peruvian journalist told us that ‘accessibility and credibility of the sources is very important’. When a source works well then it is very likely they will go back to it (Mendizabal, 2013i)

Audience development is a useful concept to understand when thinking about who will listen to a newly formed think tank. Grant-Salmon (2014) describes it like this: ‘audience development is about developing our communications with existing and new audiences, not just increasing the number of people we are talking to. By understanding and gaining knowledge about existing and potential audiences, we can develop relationships in order to communicate relevant, timely, simple messages of value. And by understanding our audiences we can build up trust and credibility so that they seek our help. We can also avoid trying to communicate with audiences who are not interested in our work.’

Finally, remember that not all audiences need to be convinced that your policy recommendations must be acted on. Some may need convincing that they should support your ideas while others may need to be supported in developing and communicating their own arguments.

Box. Tools for stakeholder mapping

Here is a selection of tools that could be useful for analysing and mapping stakeholders:

- GIZ (2010), Youth development stakeholder analysis: A handout for practitioners.

- Schiffer, E. (2007), Net-map toolbox: Influence mapping of social networks.

- IIED (2005), Stakeholder power analysis.

- Brouwer,H., Hiemstra, W. and Martin, P. (2011), Using stakeholder and power analysis and BCPs in multi-stakeholder processes.

- Overseas Development Institute (2010), Planning tools: Stakeholder analysis.

Engaging with stakeholders and counterparts

Datta (2018) offers advice for setting up your team and establishing key relationships in order to participate in projects that help counterparts and policymakers use evidence+ Based on Datta, A. (2018), Twelve tips to set up a team and establish relationships. Learn more.

- Ensure your team has the ‘right’ people and organisations: Aim for a small team of 3–4 people including: an insider with deep knowledge of the policy issue and understanding of the context; someone with facilitation skills and the networks to engage with policymakers; someone with technical skills; and a team leader who coordinates the members and brings together the technical and political dimensions of the project.

- Make the most of prior connections and shared experiences: To foster strong relationships it is important that there are expectations that something ‘good’ will happen. Having some prior contacts and shared experiences can accelerate this process.

- Base your team close to the ‘action’: The team should be as rooted as close to the ‘action’ as possible and be made up of national staff. When bringing in foreign team members, immersion in the context for long periods of time is essential for them to build good relationships with key actors.

- Establish ‘good’ team working practices: Make sure your team members communicate regularly and that they feel comfortable talking and listening in equal measure.

- Work with high-capacity institutions for short-term change: Your counterparts will be more likely to use your support if they have high levels of capacity to begin with. This doesn’t mean that you avoid institutions with lower levels of capacity, just that doing so will require a longer-term approach.

- Negotiate the role you play in relation to your counterpart: When working with partners in government, you have to decide with them how much emphasis should be placed on getting results versus capacity development. If there is a results approach you may take a more hands-on approach (managing the overall process). If the focus is on capacity building, your team may take a more reflecting approach by limiting inputs to observations.

- Listen to the needs of your counterpart but don’t set out to meet all their demands: Your counterpart has deep knowledge of the local context, but there is value in what you have to offer, so it is important to have discussions that consider different perspectives and to see each other as partners or collaborators.

- Identify and coordinate with existing in-country policy support or evidence-related initiatives: There may be other teams who are supporting policymakers to use evidence. If this is the case, try to find ways to work together, as you may find that your work is complementary.

- Consider setting up an advisory group: A steering group may help ensure that the work produced between you and your counterparts is relevant beyond the actors you work with. It can also pressure your counterparts to ensure a rigorous engagement with the process. For this advisory group you can approach institutions with a cross-government mandate or representatives of other policy support initiatives.

- Formalise the relationship between the delivery team and your government counterpart: Consider revising the memorandum of understanding that often underpin agreements between government institutions and external actors if there are areas that you would like to see changed, such as confidentiality or intellectual property clauses.

Box. Partnership toolkits

These two partnership toolkits provide advice on how to build successful partnerships through structured approaches that will help you identify the type of partnership needed and the kind of agreements you will need to reach.

- NESTA (2019), Partnership toolkit.

- Sterne, R.; Heaney, D. and Britton, B (2009), The partnership toolbox.

How will it communicate?

Starting out with your communications can seem daunting. There is a lot of noise out there and making your research stand out among all this information can feel like an uphill battle. There is also the matter of figuring out where to start, who will be in charge, and what you will communicate. There are a lot of resources you can use to communicate your research, but before you spend a lot of money on a fancy website, set up social media accounts on various platforms, or plan a big launch event, take a step back and ask yourself one key question: Who has to engage with my work in order to get my desired impact? More often than not the answer to that question will take you directly to the correct communication tool or channel.+This section draws on Grant-Salmon (2014) Audience development: Can we have a meeting to discuss the dissemination of my research report? Learn more

At the start of any project, think about what you are trying to achieve. What does success look like for your work? It is important to think about this at the start of a project. It will enable you and your team to choose the correct output to ensure maximum impact.

If you know your audience, you know how they consume information +If you do not know how your audience consumes information, do take some time in speaking with either your potential stakeholders or someone who knows the best way to communicate with them. . This will allow you to be innovative with your outputs and communication tools. It will also allow you to optimise your budget: it is better to have a small event (a breakfast meeting, for example) attended in full by key stakeholders, than a massive event where your stakeholders may stop by for a quick minute and leave without engaging. Your audience might consume information in the form of blogs, videos, briefings, virtual conferences, social media, press releases, backgrounders, infographics or one-to-one meetings – or a combination of several of these (Grant-Salmon, 2014).

After you answer this question, ask yourself: What is my budget for communications? It’s important to be realistic about what you can and cannot do. However, don’t make assumptions on costs. Don’t assume you cannot afford something just because it looks pricey or because bigger and/or older organisations can. Video is a perfect example of this: it is an excellent tool to communicate on urgent policy issues, yet organisations often think they are prohibitively expensive and shy away from producing them. Yes, they can be expensive, but you can also produce effective videos on a low budget. As with most things, it’s about doing the best you can with the resources you have available, and not aiming for a knock off. A video on a budget can look like a video on a budget and still be effective, engaging and impactful.

Box. Events

Producing events can be a cost effective way of producing new content. Here are a couple of ideas for doing so (Mendizabal, 2016):

- Search for free venues in your city. Universities sometimes lend empty rooms to their alumni, staff or students. Or you could co-organise with other think tanks – even coffee shops and restaurants lend themselves for events. Be creative and think outside the classic hotel venue and you will find many options.

- Events do not have to be elaborate; a simple room with chairs and space to present will do. And, if pressed for funds, limit the refreshments – people go for ideas, not for free breakfast (although in some contexts offering refreshments might be crucial so adapt this suggestions to your own environment).

- Keep events to the point, brief your speakers beforehand and allow plenty of time for the public to engage (and for networking!)

- Use the event as way of producing new content. You can record or web stream the event, live tweet it, upload or share presentations, write blogposts or reports on it, interview the panelists to create short videos, add attendees to your database, and so on.

An event is an incredible opportunity to do these and many other things; be prepared and think outside the box. Read more about events here: Mendizabal, E. (2015), How to produce a public event

Deciding on tools and channels

There are a lot of tools and channels with which to communicate, but keep in mind that not all of them are appropriate for all projects (or all organisations)+Section draws from Mendizabal, E. (2012b), Communication options for think tanks: Channels and tools. Learn more +Weyrauch, V. (2014), Selecting different ways to reach audiences: A strategically ongoing effort. Learn more. Each think tank has to choose the mix that works best for each project and for the organisation as a whole. There shouldn’t be a massive discrepancy between these two aspects. If your organisation is focused on specific themes and the work you produce is targeted at roughly similar audiences, there is likely to be a synergy between these two combinations. Larger organisations, however, are likely to have a wider scope on themes and research outputs and, consequently, their audiences, which means that the tools/channels combination will most likely be project-based (Mendizabal, 2012b).

The following questions can guide the process of choosing your tools and channels combination (based on Mendizabal, 2012b):

- Does the centre have the resources (funds and people) to effectively deploy all the chosen tools? For example: Does it have the media skills to deal with an important media strategy? How many events can it organise in a week? Does it have reliable access to the internet? Does it have resources for printing its publications?

- Are the tools sufficient to reach all of the organisation’s main audiences? Are any audiences not being reached through your choice of tools and channels?

- Do they offer the right balance between content and outreach? In other words, is it all repackaging or is there sufficient original material to carry the argument for a significant period of time?

- What will be the best way of keeping the organisation’s arguments and ideas on the public agenda for longer?

- Are the tools linked to and supporting each other or are they being deployed independently and in isolation?

Box. How to use your tools?

Based on Mendizabal. Communication as an orchestra.

The goal is to introduce your ideas to the public and keep them there for as long as possible, maximising your chances of being present whenever a window of opportunity opens. Think tanks need to keep their public engaged for prolonged periods of time. It is not good enough to get their attention once, at a press release or an event, never to engage with them again. They must keep journalists coming back for more, reporting on their ideas and recommendations; keep policymakers engaged in policy discussions over several policy cycles until the right policy window opens; keep other researchers involved in debates, and more. Their ideas have a greater chance of informing policy if they remain relevant and on the agenda for a long period of time.

This means that think tanks have to keep producing excellent communication outputs that they can combine to make ‘great music’ – music that is engaging, popular and interesting.

To help you with this, here is a chart showing the type of channels and tools available and how successful they can be at reaching specific stakeholders.

Table: Channels and stakeholders

Source: Weyrauch, 2014

The ‘classic’ model of disseminating information by think tanks (‘Expert or academic carries out research. Generates rigorous 40-page report. Comms officer is asked to promote said report. Launch event, press release, tweets. Maybe a video. Maybe an infographic’) is no longer sustainable. Tom Ascott +Ascott, T. (2019), New technology and ‘old’ think tanks. Learn more, digital communications officer at RUSI explains that this model is almost designed to be inaccessible to a larger and increasingly inquisitive public. Think tanks can’t rely on invite-only events or video uploads of those events. They have to compete with other online content creators and capitalise on modern digital media, turning research papers into multi-medium products.

Box. Tool: Communications health check

This tool is designed to help think tanks and research institutes to refine and improve their communications. It evaluates a number of key areas: audiences, channels, messaging, systems, strategy, capacity and monitoring.

By answering a number of simple questions, the health check will help pinpoint areas to consider prioritising to help you communicate your research and support your brand. The analysis recognises that communication is a complicated process involving strategy, tactics and resources: in other words, it is not all about output.

Size matters

When you are starting out, your communications department might look very lean. And by lean we mean a one-person show. What we do advise, and rather fervently we might add, is to do communications from the start. It might happen that you can only afford a communications manager or a communications consultant on a per-project basis. Whatever your reality is, don’t leave communications to the side. A 200+ page report doesn’t ‘speak on its own’. Neither does a 40-page document. Get your researchers on board. As Enrique Mendizabal argues in this video, ‘the thinktanker of the future is going to be a good researcher, communicator, manager and leader’.

Today’s researchers have to be prepared to wear different hats, but you cannot expect them to have the know-how already. This means you might have to invest in capacity-building opportunities to develop their skills. The bottom line is, big or small, when you are setting up a think tank you have to think about how your communications will play out: define who will be in charge and what resources she or he will have at hand.

Think tank branding

It is important for think tanks to work on their brand and ensure that they are more than a logo. Branding is key because your work as thinktankers needs to be communicated to wide audiences across different channels and it needs to carry your identity. In this article, John Schwartz explains that strong branding helps think tanks:

- ‘Become the organisations they aspire to be’: because the branding strategy extends the organisational strategy.

- ‘Own a piece of intellectual and cultural territory’: because it allows think tanks to know exactly who they are, what they are for and why what they do is important.

- ‘Produce the right kinds of communications for the right audiences’: because in order to build a brand, think tanks need to start with a good understanding of their audiences and how to communicate with them in an efficient and impactful way.

Box. Communicating research: Research isn’t linear, so why are reports?

Joe Miller makes the case for moving beyond PDFs when writing up research because they ‘box in our thinking’: they create linear narratives.

It is important to choose different tools for different communication strategies. In his article, he talks about a design based on the ‘choose-your-own-adventure’ approach: a website that allows readers to access the content from different entry points and to follow new links that might be lost in a linear PDF.

Think tanks should be creative and make use of engaging technologies, data visualisations and websites to communicate research findings.

Monitoring your communications

Carolina Kern offers some recommendations for designing a MEL strategy for communications+Based on Monitoring your communications: Try this by Carolina Kern (2017). Learn more, especially for new and small think tanks:

- Be fully clear about what you’re going to measure and why. You can do this by revising your strategic aims or policy influence objectives.

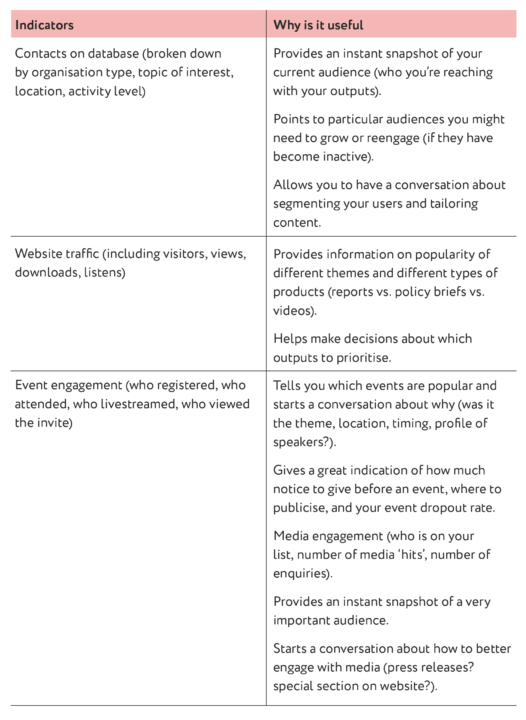

- Don’t do anything too fancy to begin with. Pick a couple of indicators and use simple tools to track them. What you choose to monitor and which indicators you use will vary, but the most useful for those new to MEL for communications are shown here:

- Have a regular (e.g. once a quarter) meeting that focuses on learning and future strategy. You can present your data in a visually engaging way to show trends and use the meeting to brainstorm ideas for future communications and to fix any issues that may have come up.

Having a clear MEL strategy can be time consuming, but it is one of the best ways to help think tanks achieve the greatest impact in the most cost effective way as long as the data collected is analysed and the lessons learnt put to use.

This Communications monitoring, evaluating and learning toolkit based on internal guidance from ODI provides a framework to think about your strategy and offers questions, indicators and tools to help. It can help ensure that your communications are strategic and that you learn from what works and what doesn’t.